The Paracas embroiderer rarely, if ever, failed to realize her end, no matter how involved her plan. We ourselves are likely to be hopelessly lost in these compositions in which pattern elements-shapes, positions, colors, and techniques-are variously combined and played over a surface with unparalleled virtuosity.”

~ Cora E. Stafford, Paracas Embroideries: A Study of Repeated Patterns

My focus on the transcendent Paracas embroideries used for ritual purposes, from study fragments to large mantles on view in the MFA’s Ancient American galleries, in tandem with reading about the subject, has taught me something about the dominant embroidery styles, which are most commonly called 1) block color, 2) linear, and 3) broad line. According to Paracas scholar Anne Paul, these three styles coexisted temporally, and were emblematic of specific symbolic and communicative purposes. This makes a great deal of sense to me as an artist: the styles are visually divergent, the fabrication choices are intentional, and respective approaches to rendering imagery result in iconographies that read very differently. Though we cannot know the true meaning these embroidered garments conveyed in Paracas culture, it’s intriguing to imagine how the differently-styled textiles may have functioned. In today’s post I focus on block color embroidery, the most varied of the three styles.

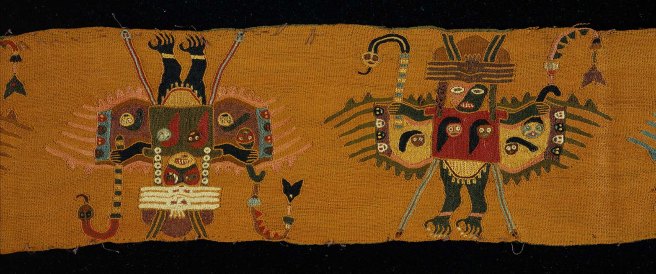

The embroidered figure above has been described as a bird impersonator – it’s not difficult to see why! Block color style embroidery allowed for the fluid rendering of readily identifiable images that were reflective of a Paracas world view and its relationship with an ecological order. The standing figure sports in colorful detail a ritual garment, mask, headdress and accoutrement thought to have been worn by a Paracas leader. Having studied the embroideries in the context of examining individual mummy bundles excavated from the Necrópolis of Wari Kayan, each of which was sequentially numbered (see blog post City of the Dead), Anne Paul shares direct observations in her book Paracus Ritual Attire: Symbols of Authority in Ancient Peru:

…In bundle 378 there are representations of ritual functionaries wearing pampas-cat skins, feline masks accompanied by vegetation, shark suits, bird capes and tails, feline-bird outfits and possibly serpent costumes. The embroidered images record the types of ritual attire that were likely to have been worn. Although examples of the actual costumes were not among the contents of this bundle, an elaborate three-tiered cape made of condor feathers was placed around the “shoulders” of Necrópolis bundle 290…The embroidered images of the costumed personages on the garments in bundle 378 represented living impersonators of cult images.”

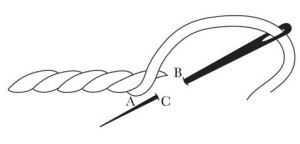

The block color embroiderer overwhelmingly favored “stem stitch” as a means to realize the descriptive imagery associated with the person for whom the textile was fabricated. Worked first with a forward moving action over the fabric surface, then backwards underneath the fabric and out again, this technique creates a series of overlapping thread segments that can delineate any type of line, whether straight or curvilinear, affording the greatest freedom of rendering imagery in a realistic, pictorial manner. The use of block color embroidery as a means of conveying a visually symbolic association between the wearer of the mantle and the figures stitched on the cloth would have been a practical choice, given the flexibility afforded by this technique.

The Paracas embroiderer first created a sketch of the figure using a single color of thread, outlining areas such as arms, legs, eyes, mouth, appendages and other compositional details. Then, by stitching contiguous rows side-by-side, negative spaces were filled in with solid colors. One can easily discern the outline stitches when looking closely at the embroidery ground. It’s also worth noting that the mantle in our collection bearing these bird impersonators has areas along the border that were left unfinished, providing process-oriented clues to the sequential steps of the embroidery process (see image below).

A distinctive characteristic of block color style is a systematic pattern of alternating configurations of a given color palette from figure to figure, as shown by the diptych below. For example, the olive green thread on the tunic shown on the left is used to color the arms and legs of the figure shown on the right; red used to color the arms and legs of the figure on the left is used for the tunic on the right. Alternating patterns of color placement from one figure to the next is applied in a faithful manner on all fifty-five bird impersonators occupying the woven ground, promoting visual dynamism and movement when viewed as a whole.

In a paper published by Anne Paul, Why Embroidery? An answer from the ancient Andes (2002), she describes what I consider to be a more compelling role of color associated with the consistent patterning of its distribution:

Apart from pure visual pleasure, color had a more esoteric function: it was used to encode a particular kind of logic in cloth. To begin with, each of the motifs embroidered on a garment is filled in with colored threads according to a master plan that specifies the color of the iconographic details of that image. This combination of colors is called a “color block”; different color blocks can be employed on a single embroidery, aligned in the field to create regular patterns along horizontal rows, vertical columns, and the S and Z diagonals, with the diagonals dominating in importance.”

The predominant “S” and “Z” diagonals that Paul refers to are terms used to denote the directional motions of spun fiber: to produce an “S” twist yarn, the fibers are spun in a clockwise direction; to produce a “Z” twist yarn they are spun counter-clockwise. In addition to the encoded logic imparted by block color patterning as described by Paul, an additional trait of Paracas embroideries are figural motions of symmetry. Paul’s hypothesis is that Paracas embroiderers, in the use of both color and motion symmetries, were expressing principles of ordering and a way of understanding spatial relationships that:

…replicate either the symmetry of fabric structures or the regular alignment of the fiber elements that comprise the fabric plane. This design choice – achieved by stitching images on cloth – underscores the importance of fabric-making processes and the vital role of weaving in their culture.

I’m deeply intrigued by the perception of Paracas embroidery style and patterning as self-referential expressions of intrinsic material structure. I plan to do more looking and reading, especially about aspects of motion symmetry not elaborated upon in this post, and will write more about the theories of Anne Paul, Mary Frame, and others who may emerge in my exploration. In next month’s post. I will also share what I have learned about another Paracas embroidery form known as “linear style.” For an introduction, see previous features from Object a Week: 02.12.18 (Man’s poncho) and 03.26.18 (Mantle), where the kinship between textile style and structure are also referenced.

A Closer Look features in-depth posts that develop from “quick studies” by the author based on Textile and Fashion Arts collections at the MFA, Boston. As such, her deeper explorations share a correspondence with many of the objects she writes about under the category Objects in Brief.