In her celebrated book Anni Albers: On Weaving, the artist writes in her Preface:

…Though I am dealing in this book with long-established facts and processes, still, in exploring them, I feel on new ground. And just as it is possible to go from any place to any other, so also, starting from a defined and specialized field, can one arrive at a realization of ever-extending relationships.

Thus tangential subjects come into view. The thoughts, however, can, I believe, be traced to the event of a thread.

Albers’ reflection on what it means for her to write about the ancient subject of weaving has been a useful anchor as I endeavor to launch this project. The inspiration for this blog had its genesis two years ago, when I started a full-time position as Department Coordinator for the Textile and Fashion Arts department at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. As a visual artist working in fiber, with a special interest in bringing process-related and other meaningful dimensions of textile arts to general audiences, writing a blog seemed a fitting way to respond creatively to my immediate environment. The project would serve to familiarize myself over time with its encyclopedic collections, to share my observations and learning, and to encourage exchanges from a community of interested and informed readers; contributing to the general corpus of knowledge on the subject of cloth.

That moment has arrived, and with great excitement I welcome you to Textiles in Context.

First blog posts (putting a stake in the ground, as a friend put it) can be difficult. This has certainly been my experience; deciding where to begin has been a humbling challenge given the vast array of topics and directions one could choose, with an impressive collection spanning thousands of years and myriad cultures within reach. In my search for a foothold, it was useful to think of a personal association. In so doing, I became reconnected with a formative experience during my nascent development as a fiber artist 26 years ago, when I had the great fortune to see my very first textile related exhibition, To Weave for the Sun: Andean Textiles in the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

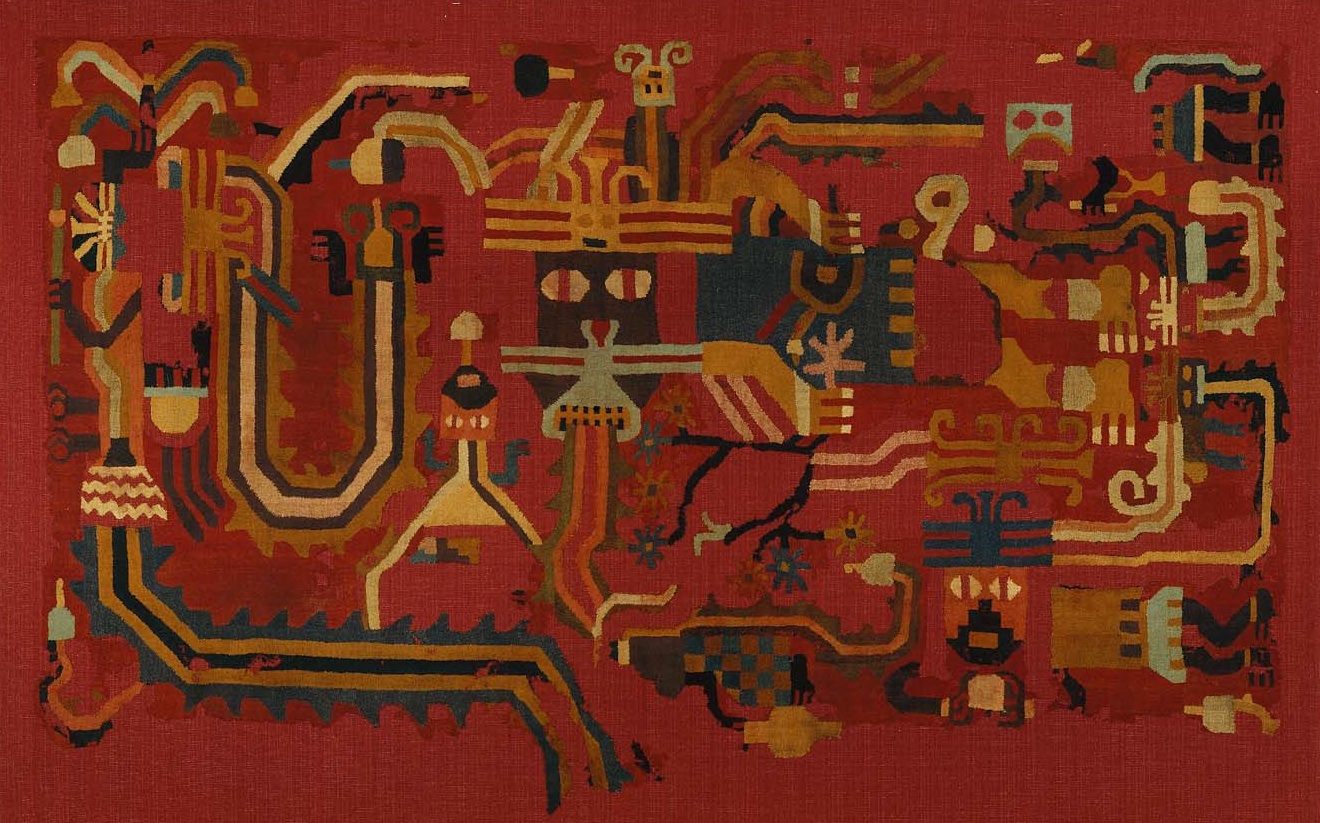

To Weave for the Sun, on view during the fall of 1992 in the MFA’s Torf Gallery, was a stunning showcase of Andean textiles in the MFA’s holdings, inclusive of Pre-Columbian through Colonial periods. I recall the dimly lit spaces, necessary to protect objects especially vulnerable to light, evoking for me hallowed mysteries and telescopic portals through time. Upon closer examination of the roughly 50 textiles on exhibit, I was mesmerized by the rich variety of iconographies, shapes, colors, geometric patterns, and the meticulous and exacting execution of complicated weaving structures made with the simplest of tools and materials: backstrap, frame and upright looms, combs, needles, spindles and bobbins, and fibers from alpaca, llama, guanaco and vicuña. My renewed exposure to these collections has increased my awareness of their significance. Rebecca Stone-Miller, in her introduction to the exhibition catalog, writes:

Although many artistic media were integral to Andean life and expression, textiles acted as a foundation for the entire aesthetic system to a degree unparalleled in other cultures of the world. Textiles were invented and developed long before other media, played a seminal role in the development of “civilization” itself, and continued their preeminence for thousands of years…The intensive efforts involved in gathering and processing materials, the extensive exploration of techniques, and the overall society was dedicated to fiber.

Numerous textiles, many demonstrating the most complex and virtuosic weaving structures known to this day, as well as intricately executed embroideries covering large areas of finely woven cloth, were miraculously preserved in the arid sands of the Peruvian coastal desert, where they were buried with the dead. Here, they remained undiscovered for close to 2,000 years before landmark archeological excavations were conducted in the early 20th century.

Of the Andean textiles I first encountered in To Weave for the Sun, those from a particular culture stood out for me by merit of their richly detailed, colorful, and highly elaborated symbolic imagery: embroidered textiles from the Paracas peninsula of the Peruvian southern coast. I remember with great clarity the expressive and somewhat hallucinatory images of flying beings, cats, birds, snakes, and anthropomorphic figures (combination human/animal), often holding severed heads (cited in the literature as “trophy heads”); images conjuring worlds within worlds. In next month’s post, I aim to take a closer look at these embroideries and delve deeper into aspects of their brilliant iconographies. Though we cannot be certain of the true meaning of this imagery, the literature about Paracas embroideries presents fascinating interpretations that I look forward to reading more about.

Another topic I hope to explore further is a weaving practice known as “discontinuous warp and weft,” a technically challenging technique not used anywhere in the world outside of Peru. Unlike the Paracas embroideries, in which image content is created using a super-structural application (embroidery yarns anchored to a woven cloth foundation), discontinuous warp and weft is an elaborate structure of the woven plane itself. Here, both the warp (vertical yarns under tension) and the weft (horizontal yarns inserted through the vertical) are discontinuous; meaning, they do not travel the full fabric width or length from one end to the other. It is a difficult fabric to produce, necessitating the use of “scaffolding” threads or small sticks, especially in the building of curvilinear shapes. Readable patterns in weaving are more commonly achieved when either the vertical warp threads (warp-faced fabric), or the horizontal weft threads (weft-faced fabric), are dominant. With discontinuous warp and weft, the result is a cloth that demonstrates an equal partnership shared by both warp and weft yarns in the rendering of clearly delineated areas of color and shape. Here also, thoughtful interpretations have been published as to why this method was chosen and its possible significance. I look forward to studying examples of discontinuous warp and weft textiles in our collection to better understand this weave structure.

The Andean textile collection at the MFA, comprising over 350 objects spanning nearly 2,500 years, ranks among the most comprehensive collections of its kind worldwide. I was very interested to learn that surviving Andean textiles to date form the longest continuous textile record in world history, spanning as far back in time as 3,000 B.C. to the present. I return to the words of Anni Albers, who believed her thoughts on weaving “can be traced to the event of a thread.” For Albers, regarded by many as the paramount textile artist of the 20th century, it comes as no surprise that her seminal book is “Dedicated to my great teachers, the ancient weavers of Peru.”

For me, this is where it starts. I invite you to follow me on Textiles in Context and join me on this quest!

A Closer Look features in-depth posts that develop from “quick studies” by the author based on Textile and Fashion Arts collections at the MFA, Boston. As such, her deeper explorations share a correspondence with many of the objects she writes about under the category Objects in Brief.