In the absence of any written texts, woven and embroidered fabrics and ceramic pottery are all that remain of Paracas civilization. It has been a privilege to look closely at textiles in our collection that miraculously survived for nearly two millennia; ritually buried with their dead in the arid sands of the Paracas Peninsula, protected from the vicissitudes of light and moisture. Exploring the intriguing Paracas embroideries of ancient Peru has made me familiar with some of the theories and interpretations about how these textiles may have functioned within the culture. The piecing together of actual details is difficult, but the stories that I find most interesting are those that weave themselves into textile structure itself for clues.

A comparison of two formally and iconographically different embroidery styles is one way of understanding the ways these textiles transmitted discrete knowledge within the society. In my blog post A Hidden Order, I wrote about the distinctive block color embroidery–a highly expressive, flexible, and pictorially detailed style of fashioning images onto cloth (see images above and below). Here, embroidery is worked in stem stitch to both outline and fill in the negative spaces of compositional details such as arms, legs, eyes, mouth, costume elements, wings, appendages, and the backgrounds of borders. Figures embroidered along borders and on the woven field portray humans in costume, supernatural beings, animals and anthropomorphic figures in vivid colors, allowing for the depiction of real, physical objects from direct observation.

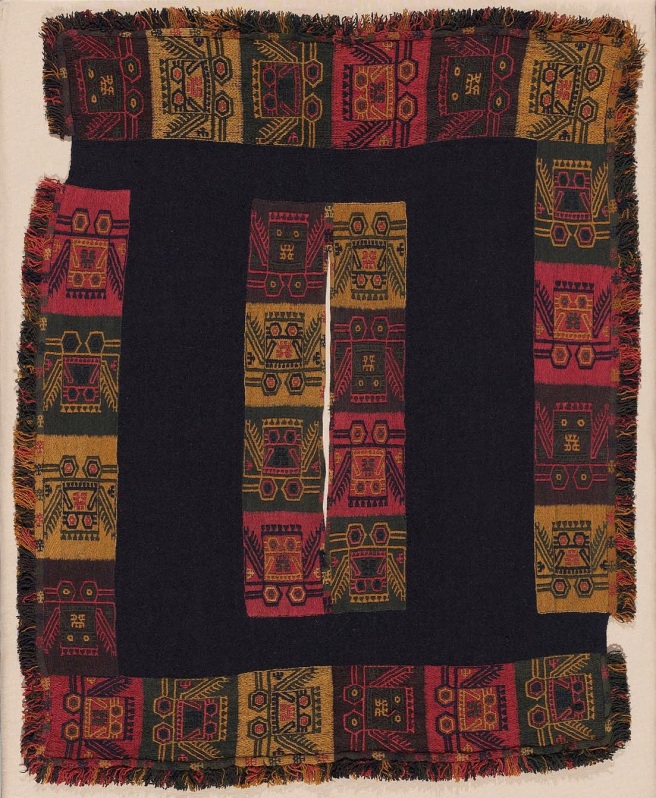

Another style called “linear” embroidery (see image below) is conceptually and visually divergent from block color style. Whereas block color embroidery is characterized by freehand, curvilinear stitches to identify realistic shapes and figures, linear embroidery stitches faithfully follow the warp and weft pathways of the woven ground, resulting in figures and patterns that are geometric. In the linear style, the background is created first with a series of parallel-running stem stitches. Images emerge as negative spaces that are then outlined with contrasting colored yarns. In this manner, both figure and ground are built up simultaneously, and distinctions between the two are more subtle.

Anne Paul, who I cite extensively in my posts on the Paracas embroideries, tells us in her book Paracas Ritual Attire: Symbols of Authority in Ancient Peru that formal and iconographic elements of linear style embroidery are consistent from sample to sample, with some designs transmitted over the duration of many generations, without major changes. She considers the fabrication process to explain why such designs would resist innovation over time:

The design plan of linear style embroidered images was conceived as though it were woven: the artist counted the particular sequence of warps or wefts to be covered by thread in each row of the background. Thus, a design could be counted out, assuring iconographic and formal consistency among the same type of images.”

Referencing block color embroidery as a means to depict realistic imagery, Paul compares this fluid working method to the opposing linear style method that aligns itself along the structural matrix of woven fiber– and thereby explains how this latter process, resulting in conventionalized symbols, plays a role in the transmission of a different form of cultural knowledge:

The procedure for creating a linear design implies that the image was not thought of as an entity separate and discrete from the background, since figure and ground were built up together; it was a method of working that was not suited to the copying of forms in nature. It is as if, in terms of working procedures, the linear style were more appropriate for the description of non-perceptual knowledge, as if the images were derived originally from non-visual sources. In fact, the images depicted in linear style are more generic in character, compared to the specific block color designs, which depict species of animals and details of costuming.”

Paul considered the disparate embroidery styles as encoding different types of information. In my blog post A Hidden Order, I included comments she made based upon her actual observations of Necrópolis mummy bundles, where she proposes that block color figures portrayed on embroideries found buried with their dead (for example, bird impersonators) represented the deceased person in life; establishing an association with a particular cult entity. The flexible rendering of pictorial images by use of this style fulfilled this purpose. Looking at linear style embroideries, Paul postulates how these functioned as communicators of traditional meaning:

…the method did have a potentially important advantage: the creation of a pattern encoded in a formula that was in turn governed by the structure of the cloth guaranteed a regular repetition of the image. Once the sequence of stitches for every row was learned, it was relatively easy to repeat the design consistently. This would have been an advantage if an image carried traditional meaning, necessitating repetition without variation through time.”

Linear style embroidery that employed the woven plane as a master template for both the number and direction of stitches, building geometric forms that mirror the essential structures of woven fiber, encoded a different type of message that by its nature, was more abstract and universal. I end this post with a final thought from Anne Paul about the role linear embroidery style may have served in maintaining the continuity of traditional knowledge in Paracas culture:

The formal characteristics of linear style images—that is, the stylistic features that make them visually elusive—together with the presence of iconographic conventions used in ancient Peruvian art to indicate supernatural status and the absence of elements of costume and details that allow identification of animal species, suggest that linear style images are supernatural and mythical rather than physically real objects…

…This style was highly symbolic, a vehicle for the communication of abstract information. The types of abstract information that could be made visible through a conventionalized style would be such things as the names of ancestors; lineage, clan, or family names; and symbols of community supernaturals or nature spirits. Images carrying expressive content of this sort would produce patterns of distribution over time that conform most closely to those of linear style images: they likely would be represented over long spans of time in an unchanging way, and although there would not be a need for many different images, the existing images would be shared by many persons over many generations.”

A Closer Look features in-depth posts that develop from “quick studies” by the author based on Textile and Fashion Arts collections at the MFA, Boston. As such, her deeper explorations share a correspondence with many of the objects she writes about under the category Objects in Brief.