The story of Haida artist Evelyn Vanderhoop, entwined within the threads of her weaving practice, is one of cultural survival. Her life as an artist, educator, mother and grandmother bears legacies of traditional knowledge and meaning that reaches back to her mother, to her mother’s mother, and journeys forward with her daughters who have young children of their own. Re-working the fragmentary threads of a forgotten practice, these Haida weavers across generations have regained and are actively sustaining an ancestral tradition that was lost for nearly two hundred years—the tradition of the Raven’s Tail chief’s robe, Yeil Koowu, a historic Tlingit ceremonial dance blanket, the design and execution of which was fixed exclusively within the realm and responsibility of women.

The revival of the Raven’s Tail tradition from its mysterious fall from practice is itself a compelling story of re-discovery, reverberating within the ripples of knowledge transmission and the preservation of Native culture. Its resurgence during the 1980s was catalyzed by Cheryl Samuel, a weaver, educator, author and native of Hawaii. She was among those receiving meritorious service awards last spring 2019 by the University of Alaska Southeast for her role in bringing the practice to Alaska Native Elders. Her exceptional dedication to the tradition is underscored by her adoption in the year 1991 into the Strong family of Klukwan, the Mother Village of the Chilkat Tlingit. She is a member of the Kaagwaantaan Clan, Eagle/Wolf, and was given the name of a weaver from the mid-1800’s: Saantaas, or Ancient Threads. Her discovery of the lost practice came by way of studying Chilkat (naaxiin) style weaving, a later formline art that evolved from the Northern Geometric style (another name for Raven’s Tail). When she became aware of this latter style, she realized it seemed quite rare and not part of any Native tradition that she knew.

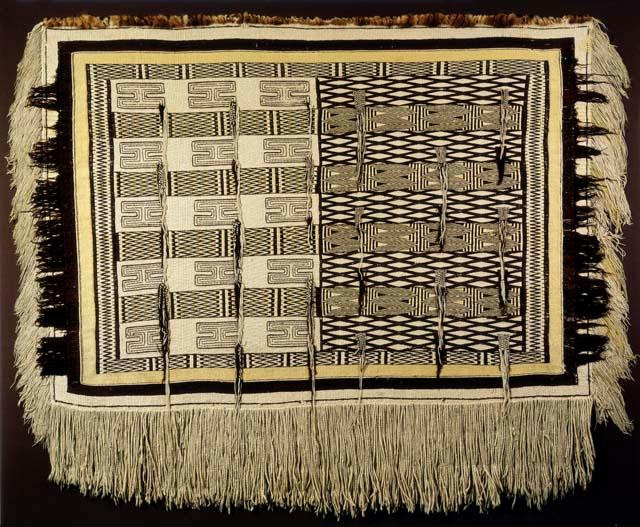

The auspicious re-awakening of the Raven’s Tail dance robe is all the more miraculous when one learns how few exist historically. Only eleven robes, or dance blankets made during the late 18th-early 19th century remain: they are stewarded by museum collections scattered throughout the world. Seven of these robes exist in fragments, and two can only be observed in the form of illustrations made by early explorers. One of two in North America survived intact, and today exists in near perfect condition—the “Swift” robe, named after Captain Benjamin Swift of Massachusetts who acquired it around the turn of the 19th century while on a trading mission to the Northern Pacific coast. The blanket is housed at the Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology at Harvard University and considered to be the finest historic example known; aside from its excellent condition, it displays the majority of techniques and pattern forms known to the Northern Geometric tradition. Of special significance to this story is the visible kinship between the “Swift” blanket and the dance robe made for the MFA, Boston by Evelyn Vanderhoop. By her own account, this historic chief’s robe was a special object of study and personal interest during her early exposure to Raven’s Tail weaving—passed down to her by her mother, Delores Churchill. Both robes are designed with two distinct halves bearing specific meaning. According to tradition, each side was intended to deliver a particular message to a viewer who would see one side of the robe at a given vantage point while being danced. Depending on who that person was, the message might be favorable…or not so favorable!

Gripped by an obsession to get up close and personal with the last surviving Raven’s Tail robes, Samuel’s mission to experience them through object-based research was guided by her chief goal to document their forms, allowing for their re-creation in contemporary times. She embarked on a quest that lasted seven years, traveling to museum collections in Europe, Canada and the U.S. to study the textiles’ structures and experience their power. The depth of her personal journey is epitomized by the introduction to her book, The Raven’s Tail entitled, “The Gathering of the Robes.” Her search to locate the eleven historic robes is characterized as an odyssey touched by magic: “It was almost as if the robes themselves wished to come forth and be counted.” After her extended period of sleuthing and direct encounters with these rare objects, she endeavored to weave a Raven’s Tail robe herself in order to fully understand its structure. She chose to bring to life a dance blanket that existed by way of illustration alone—the “Kotlean” robe, worn by Chief Kotlean of Sitka, Alaska as represented in a watercolor painting by Russian artist Mikhail Tikhanov (c.1818–1819) entitled, “Kotlean.”

Each of us wove slightly differently; to keep the tension even, we changed places every day. The most difficult part was measuring the space between the weft rows and keeping them parallel to the heading. Each of us had a different concept of measuring. Eventually we made three tiny, identical templates of yellow cedar bark which measured exactly the distance between the rows. Working in this way, we completed the next two patterns, learning how to move the spiral wefts efficiently, learning a lot about each other, laughing together…The experience of creating this robe gave body to the technical knowledge I had been gathering; when it finally danced we felt the impact of a Raven’s Tail robe in motion.”

– Cheryl Samuel, from her book, The Raven’s Tail

The powerful continuum of shared knowledge and education necessary for the revitalization and preservation of Raven’s Tail weaving is at the heart of this story, as is reverence for tradition, respect for the ways and teachings of ancestors, and hope for future generations to honor and carry these legacies forth. Jennifer Swope, Assistant Curator for Textile and Fashion Arts, has organized a rare opportunity for visitors to experience this firsthand in a highly-anticipated exhibit rotation in the MFA, Boston’s Native American gallery. Beginning in November 2019 and continuing for one full year, the historic “Swift” blanket from the Peabody Museum at Harvard will travel to the MFA to join Evelyn Vanderhoop’s commissioned robe and a Raven’s Tail tunic woven by her mother, Delores Churchill. On display together for the first time, they will be in intimate dialogue with one another, demonstrating the miracle of cultural survival and continuity. To offer a fuller context for what emerged from the Northern Geometric weaving style, this rotation will also include the MFA’s only Chilkat (naaxiin) blanket from November 2019-May 2020.

The patterns and forms of the Raven’s Tail tradition, defining centuries of traditional Tlingit knowledge and meaning, carry within them the expansive capacity for improvisation and personal expression at the hands of the weaving artist. Evelyn Vanderhoop’s masterwork, inspired by the “Swift” robe as its basis, embodies this jewel of creativity—an infinitely evolving process unique to the artist’s impulses and convictions that contribute to the ever-deepening richness and beauty of her Native culture. My third and final post in this series will take a closer look at Vanderhoop’s artistic process and her choices that inform the range of vocabularies twined within the MFA’s Raven’s Tail blanket—a labor of love that she has called her “Sky” robe.

A Closer Look features in-depth posts that develop from “quick studies” by the author based on Textile and Fashion Arts collections at the MFA, Boston. As such, her deeper explorations share a correspondence with many of the objects she writes about under the category Objects in Brief.

Feel so honored to have had the experience of being taught by Delores Churchill and two of her daughters, Holly, for teaching me so willingly cedar bark weaving and Evelyn for introducing me to Raven’s tale and all three of them for sharing so many valuable stories of weaving and cultural life shared through design descriptions and reasons behind them. They are each wonderful teachers having their own individual styles. I am proud and feel so privileged to know them and continue to be inspired by them. Thank you so much. Nancy Olson

Nancy, I so appreciate your comments and thank you for sharing them on this forum. You are so lucky to have had these wonderful teachers, and all they have given you. Their generosity has made it possible for you to play a role in the preservation of these traditional forms and the stories they tell. What an inspiring gift!

Again, an aspect of American fiber arts that I have never thought much about. I love the way you cover the whole picture, especially about the history, uncovered and recovered by the persistent focus of Cheryl Samuel. Thanks, Catherine. I really appreciate this article.

Thank you Suzanne, I appreciate your comments!